This article originally appeared June 23, 2017 in In These Times:

Rethink This Iowa: Do Not Gut the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture

Since 1987, the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture (LCSA) in Ames, Iowa, has been looking into ways to reduce the environmental impact of food production. Applying a scientific approach to ethical land use, the center has been funding the research needed to make sustainable farming methods not just possible, but profitable. Long before the “good food movement” grew into the national force it is today, their work included the implementation of integrated pest management techniques, bioreactors, cover crops, early spring nitrate tests, crop rotations, rotational grazing methods and much more—the results of which were shared with farmers and other researchers across the country.

All was going well enough until April 17, when the Iowa Senate without warning passed new legislation that ended LCSA’s funding and, going one diabolical step further, required the center to close. The funds in play—about $1.3 million annually—are generated from a fee imposed on nitrate fertilizers and pesticide registrations under the 1987 Iowa Groundwater Protection Act. The new bill instructs that those funds be redirected to the Nutrient Research Center, also at Iowa State University (ISU). On May 12, however, in one of his final gubernatorial acts before becoming the Trump administration’s ambassador to China, Iowa Gov. Terry Branstad (R) vetoed the portion of the bill he’d previously signed requiring LCSA to shut its doors, but let the funding cut stand.

This leaves the center in awkward limbo—free to continue existing, but without the money it needs to operate. As one writer put it in a Milwaukee Journal Sentinel editorial, the bill renders LCSA “the Walking Dead of state agencies.”

“While we appreciate that the name and the Center will remain,” said LCSA Director Mark Rasmussen in a statement addressing their sudden change in status, “the loss of all state funding severely restricts operations and our ability to serve our many stakeholders.”

So why, when industrial agricultural practices pose an immediate threat to Iowa’s land and water, and when our dominant food production methods are causing a host of ecological, health and social problems across the country and around the world—did the Iowa legislature decide to end public support for one of the few forward-thinking sustainable agriculture institutions with an established track record? The center’s mission, after all, is: “To identify and develop new ways to farm profitably while conserving natural resources as well as reducing negative environmental and social impacts.”

“We have no idea who were the primary sponsors of the bill,” LCSA Communications Director Carol Brown tells Rural America In These Times. “All we have heard is that the legislators had to make budget cuts, and that the Center was doing research that could be handled through Iowa State’s Nutrient Research Center.”

Dennis Keeney, LCSA’s first director from back in the day, was a bit more candid. Chalking the center’s deathblow up to the Iowa Senate politically accommodating powerful agricultural interests in the state, he told a public radio reporter: “They know if they put money in the Nutrient Center nothing will happen that will really lead to regulation.”

What the Nutrient Resource Center (NRC) will actually do with its new funding remains to be seen. Kamyar Enshayan, an educator from the University of Northern Iowa who served on LCSA’s advisory board back when the NRC was established in 2013, is not optimistic. In a letter to the editor of the Des Moines County Register, he calls the NRC’s creation in the first place a “big mistake” and says it’ll probably continue to make it easier for Iowa to downplay its mounting environmental problems.

Enshayan writes:

It [the Nutrient Center] renamed the tragedy of industrial agriculture (soil erosion, water pollution, deliberate evading of public health and labor laws by multinational meat packing plants or by absentee owned egg factories, public health threats from massive hog confinement operations, pesticides and fertilizer in drinking water, manure spills, etc.) as simply a “nutrient” problem.

Clearly, nutrients leaking from modern agriculture is a symptom of a cropping system that is inherently leaky, meaning there isn’t a whole lot farmers can do to stop the leak. That leaky cropping system has been planned and incentivized by federal programs, shaped by global grain merchants who also happen to control all grain markets as well as seeds and inputs. It is well-documented that it is this system, this colonizing economy, that continues to lead to rural decline.

Indeed, in addition to fomenting rampant income inequality, most of the dominant economic forces in this country have a serious pollution problem on their hands. That’s not necessarily new, but increased public awareness is. While no one regional center is equipped to address the magnitude of a given sector’s unsustainability, and it would be foolish to imply otherwise, serious progress will vary depending on the sincerity of those behind the efforts to do better.

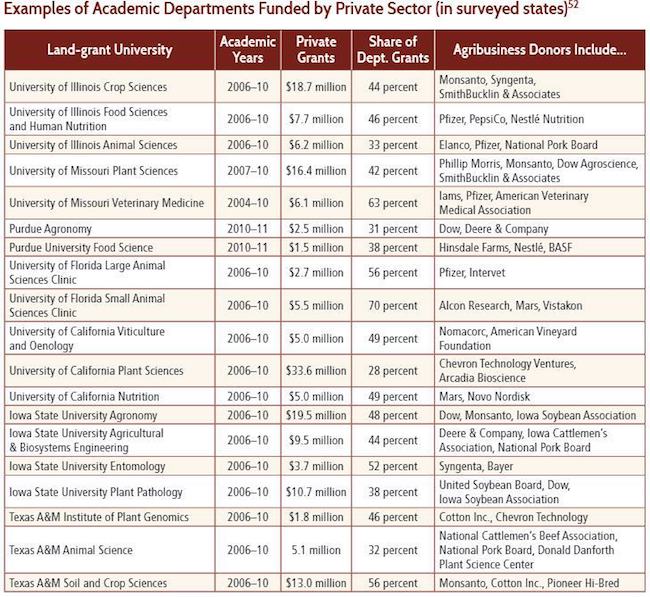

The funding of departments, buildings and research centers in universities across the country has allowed wealthy corporations to “give back” in some conspicuous, potentially good ways. But there’s plenty of evidence that many of these vested interests have “infiltrated academia”—operating under an unspoken expectation that any study a corporation helps fund ought to draw industry friendly conclusions. (From 2006 to 2010, for example, the ISU’s own Department of Agronomy received $19.5 million from donors such as Monsanto, Dow and the Iowa Soybean Association.) Whatever the case, when it comes to taking sustainability seriously, things are not changing fast enough.

Meanwhile, more than 30 new LCSA grant projects, already approved to begin in February, are on hold. Management of these projects is being transferred to the ISU College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, which, according to an LCSA press release, “has been charged with winding up the center’s affairs by the end of the 2017.”

For more information, check out “Public Research, Private Gain: Corporate Influence Over University Agricultural Research.” (Source: foodandwaterwatch.org)

Re-designing ecosystems has consequences

Iowa feeds a lot of people, animals and cars. The Hawkeye state is home to 88,637 farms. They grow (and export) more corn and soybeans, raise more pigs and produce more eggs than any of the other 49. Much of the grain is used for livestock feed and ethanol and consumed elsewhere but, all told, the annual (all important) “economic impact” of Iowan agriculture is $30.8 billion dollars—second only to California.

This is no accident. From the 1830s on, the Iowa landscape as we know it today was designed for food production—first with plows and then with steam shovels. Before that, Richard Doak writes in the Des Moines County Register, “Legend has it the region was so wet that one could canoe from Mason City to Fort Dodge.” In other words, before it could become “the Heartland,” Iowa needed to be drained.

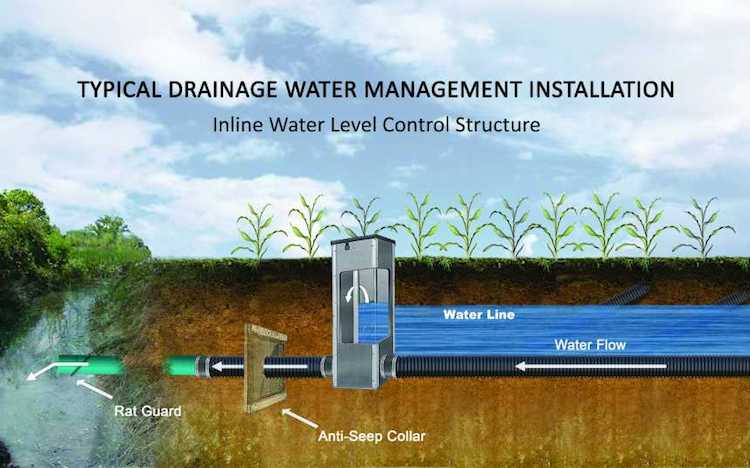

Even by the turn of the 20th century, much of the farmland for which the state is now famous was still, from an agricultural perspective, unworkable swamp. But in 1908, engineers began installing a massive underground network of tiles—perforated pipes set under future fields to funnel the prodigious moisture out of the soil and into other pipes or ditches where it could be carried away into creeks, streams and rivers.

This worked—presto primo farmland—and today this labyrinthine drainage system runs under 12 million acres of Iowa fields.

(Infographic: PrecisionAg)

Times have changed

One century (and a couple of world wars) later, modern agriculture is a very different enterprise than it was back then. Industrial agribusiness—a global juggernaut up to its neck in petrochemicals, genetic experiments, pesticides, herbicides and snacks—is, itself, hungry.

Quick recap: This paradigm began in earnest after World War II when brand new chemicals, created for war and fresh off the battlefield, were successfully marketed for use on the farm to kill bugs and weeds, thus allowing concentrated monocultures to thrive. Later, maximizing the number of animals you could keep in a confined space also somehow became a good idea. Put simply, soil, air and water quality, biodiversity, and healthy rural economies were sacrificed in order to produce lots and lots of the same few commodities.

An aerial view of a concentrated animal feeding operation. (Image: prezi.com)

Small farms dropped like dominoes after that. But it’s the synthetic inputs required to keep producing the same things in the same places over and over again—all too often as a means to keep overly-processed food cheap and profitable for multinational corporations—that are taking a cumulative and devastating toll on top-soil, waterways and, increasingly, public health.

Zero of this is good for the land, water, animals or you. While a lot can be said of American farming methods, “sustainable” is not one of them. Water supplies across the country are literally being poisoned, as are this planet’s lakes, rivers and oceans.

An enhanced satellite image showing how poor water quality in the central United States—including Iowa—can have a cumulative impact in creating a “dead zone” in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Red dots indicate large cities and green areas indicate farmland. Water pollution—notably nitrates used in farming—flow downstream where each summer they create a zone near the mouth of the Mississippi River that’s so low in dissolved oxygen it can’t support marine life. The most intense areas of the dead zone are shown in orange and yellow. (Caption / Image: The Gazette / NOAA)

Cause and effect

In Iowa, factory hog farms are storing hundreds of thousands of gallons of animal waste in giant pits (the industry prefers to call them lagoons) that tend to flood when it rains. And each year, as a result of the tremendous amount of corn and soybeans grown in the state, nearly all of it genetically engineered, tens of thousands of tons of fertilizer nitrates leach into Iowa’s waterways. The state’s previously ingenious drainage system—essentially acting as a syringe injected into their rivers—drastically cuts the time pollutants have to get absorbed.

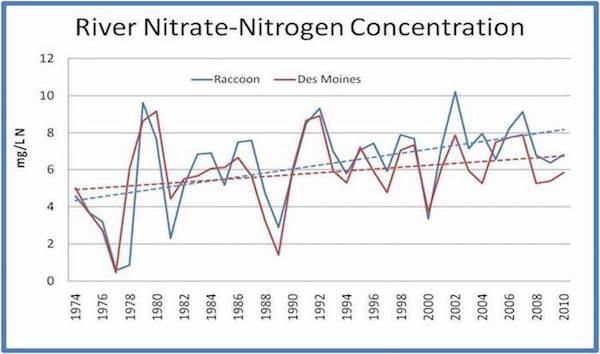

The concentration of nitrate in the Raccoon and Des Moines Rivers has been rising for decades. (Chart: Iowa Environmental Council Blog)

Unsurprisingly, contentious lawsuits over who is responsible for cleaning up the contaminated water abound. The most recent case involved Des Moines Water Works (DMWW)—a regional water utility company that, in 2015, sued drainage districts in three different Iowa counties. The charge: allowing the Raccoon River, a major source of drinking water for 500,000 Iowa residents, to become polluted with unsafe levels of fertilizer nitrates. In 2016 alone, the utility maintains, they had to spend $80 million removing nitrates from the river in order for it to meet federal drinking water standards.

Arguing that those responsible for generating the contaminated runoff (intensive farming operations) should be the ones paying to filter it, DMWW hoped to convince the courts to regulate the fertilizer nitrates as pollution under the Clean Water Act.

Here’s a brief rundown of the controversy, courtesy of PBS:

(Video Source: Newshour)

In March, after a two-year fight and plenty of unwanted attention, and despite widespread public support for DMWW, Iowa judges sided with Big Ag’s interests and dismissed the utility’s lawsuit in its entirety. The nitrate problem remains unaddressed and agribusiness as usual continues.

Ironically, one legislator seeking to justify the state’s decision to cut LCSA’s funds recently remarked that the center’s “work was completed.” Carol Brown tells Rural America In These Times that the timing of that comment, just weeks after the DMWW lawsuit ended, “has led to many Iowans scratching their heads.”

Letting Leopold down

The fact that everything within an ecosystem is connected was not lost on Aldo Leopold—the Iowa-born naturalist, scientist, ecologist, philosopher and author after whom LCSA was named. He understood that fundamentally altering a landscape will always have unintended consequences and subsequently determined: “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

In A Sand County Almanac, widely hailed as one of the most important environmental books of the 20th century, Leopold also writes:

One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds. Much of the damage inflicted on land is quite invisible to laymen. An ecologist must either harden his shell and make believe that the consequences of science are none of his business, or he must be the doctor who sees the marks of death in a community that believes itself well and does not want to be told otherwise.

Today, 500,000 Iowans who depend on the Racoon and Des Moines rivers for their drinking water are in the process of getting an all too visible, totally unwanted ecological education courtesy of industrial agribusiness. Defunding the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture at a time when the work they do is clearly needed more than ever seems an awful lot like adding unnecessary insult to ongoing injury.

(Illustration: Brian Duffy / brianduffycartoons.com)

“Ethical behavior is doing the right thing when no one else is watching—even when doing the wrong thing is legal.” – Aldo Leopold